Campus Headlines

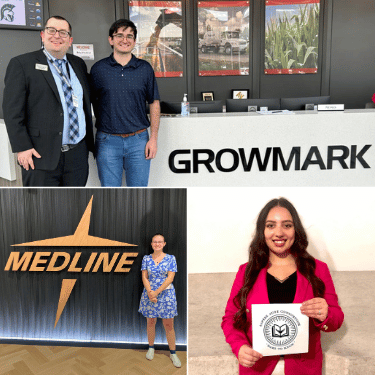

Career Center Supports Students Through Internships, Workplace Exploration

After a summer away from campus, many Illinois Wesleyan University students returned with something new on their resumes: practical work experience.

Brian Gegel '94 to Receive Alumni Nursing Award

Brian Gegel ‘94, a celebrated practitioner, professor and researcher of both civilian and military nursing, has been chosen to receive the 2025 Distinguished Alumni Award for Excellence in Nursing.

Nancy Steele Brokaw '71 to Receive Alumni Humanities Award

Nancy Steele Brokaw ‘71, a lifelong playwright and champion of the arts, is the recipient of this year’s Distinguished Alumnus in the Humanities Award.

Ed Rust '72 to Headline Inaugural Kinder Brothers Speaker Series

Thanks to the generosity of the late Jack '50 and Garry Kinder '55, the IWU School of Business and Economics will host the inaugural Kinder Brothers Distinguished Business Speaker Series featuring Ed Rust Jr. '72 as the keynote speaker.

IWU Welcomes Largest Incoming Class in 15 Years

Illinois Wesleyan University welcomed its largest incoming class in 15 years for the 2025-26 academic year.

New Students Welcomed Into Titan Traditions

Illinois Wesleyan welcomed its newest Titans this week, introducing them to the traditions that define campus life ahead of the 2025–26 school year which begins Monday.

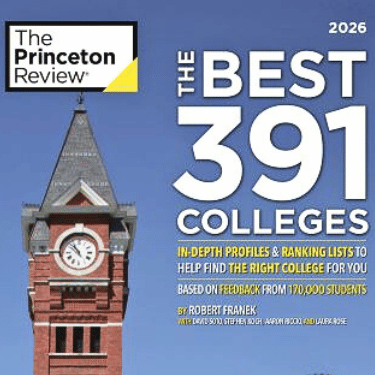

Princeton Review Recognizes Illinois Wesleyan Among Nation’s Best Colleges

Illinois Wesleyan University is one of the nation's best institutions for undergraduates to earn their college degree, according to The Princeton Review’s 2026 college guide, The Best 391 Colleges.

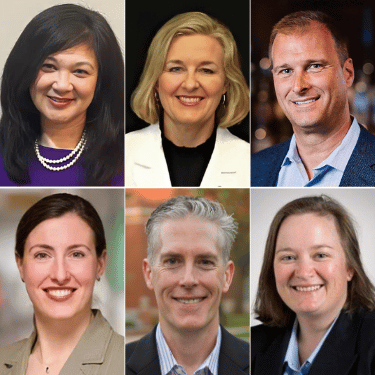

Six New Members Join IWU Board of Trustees

Six new members have been elected to join Illinois Wesleyan University's Board of Trustees in 2025.

Alumni Share Strategies for Bridging Entrepreneurial Education and Careers at National Summit

High school educators from across the country gathered for a national conference in Chicago earlier this month where a panel that included Illinois Wesleyan alumni shared insights on ways students can be guided through an entrepreneurial education...

Student Athletes Set New Record for Academic All-America Selections

Titans have set a new school record for their high achievement in athleticism and academics. Sixteen Illinois Wesleyan University students have been named as Academic All-Americans for the 2024-25 school year.