Faculty, Alumni and Students Shaping the Field of Canine Cognition

Dec. 11, 2020

BLOOMINGTON, Ill. — Illinois Wesleyan University Associate Professor of Psychology Ellen Furlong has fostered a new generation of researchers passionate about dog cognition, including Sydney Rowley ’20, Zach Silver ’18 and Ellen Stumph ’19 — all of whom presented research at Yale University’s dog cognition workshop earlier this year.

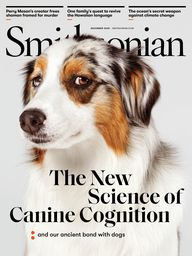

Silver’s research was subsequently featured in December’s Smithsonian Magazine cover story. The feature story, titled “The New Science of Our Ancient Bond with Dogs,” highlighted Silver’s study of how dogs make judgements in ways that are strikingly similar to human beings.

“I think intention may play a large role in dogs’ evaluation of others’ behavior,” Silver told Smithsonian in reference to his recent publication, co-authored by Furlong, on canine prosocial behavior. “We may be learning more about how the dog mind works or how the nonhuman mind works broadly. That’s one of the really exciting places we are moving in this field, is to understand the small cognitive building blocks that might contribute to valuations.”

Silver’s work marks just one avenue of potential study in this emerging field. Research projects presented at Yale’s dog cognition workshop explored a range of questions about the extent of canines’ capabilities, from whether dogs have an awareness of someone else’s beliefs to how existing tests in human developmental psychology might apply to canines. The conference, which took place in February before the implementation of COVID-19 travel restrictions, consisted of about 20 presenters from across the nation, making Illinois Wesleyan’s presence all the more impressive.

“As it was my first time at a conference with a very intimidating prestige to it, I felt comforted by seeing so many friendly faces and relieved that I got to present to supportive friends,” said Rowley, who presented as an Illinois Wesleyan senior. “I also felt proud to see our small school having made such a remarkable influence at a national conference.”

"Our students do amazing work and to be able to see alums at professional conferences and doing so well in our field made me so proud,” said Furlong. “It’s a great honor to be able to work with students throughout their careers here and then see them successfully launch into their next phase. I was proud to present alongside IWU students — past and present."

For many of these alums, Furlong was a shaping influence from the beginning of their IWU educations, with her mentorship opening the door to a host of research opportunities.

“I can still remember meeting her in her office during my freshman year so vividly,” said Stumph, currently lab manager at Yale’s Canine Cognition Center. “I told my academic advisor that I was interested in studying animals and he pointed me in Dr. Furlong's direction. From there, Dr. Furlong did everything in her power to help me grow and refine my research skills as I continued as an undergraduate. Dr. Furlong sees the potential in her students and pushes them to be their best; I don't think I would be anywhere close to where I am now without her.”

Furlong runs IWU’s Dog Cognition Lab, one of a handful scattered across the globe, which provides her students with the opportunity to conduct research with the aid of dog volunteers from the Bloomington-Normal area. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dog Cognition Lab research has continued by analyzing submitted videos. Furlong also teaches an annual May Term course focusing on Barbary macaques in Gibraltar.

By studying the minds of nonhuman animals, we not only gain an appreciation for the complexity of these animals, but also an understanding of how to practically apply this research, as Stumph has discovered through her lab’s current work with service dogs in training.

“While our research is mostly motivated by uncovering the origins of human uniqueness, I think a lot of what we learn through the process can help us better understand our relationships with nonhuman animals,” said Stumph. “I think the more we learn about the way nonhuman animals think, the better we can adapt our treatment of them to fit their needs in whatever context that may be.”

“Animals are remarkable in their capabilities beyond what we ever knew was possible,” Rowley added. “Nonhuman research allows humans to look outside themselves and understand the world around them in new ways.”

Though animal cognition is a relatively niche field, the experience of conducting independent research from start to finish has prepared these students for graduate-level work in a range of areas.

“I feel grateful to have completed my thesis in a field different than my own because it enabled me to create methods for a notoriously difficult subject - animals,” said Rowley, who currently works with Bloomington’s homeless population through PATH Crisis Center and plans to pursue a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. “I look forward to using my background in doing undergraduate research by applying it to human subjects, specifically people with serious mental illnesses. My work at PATH and experience in research with dogs has fueled my passion to further research mental health and homelessness.”

“I think one of the most enjoyable things about this research is the excitement that so many people have for it,” Stumph concluded. “It is really great to work with dog owners who are interested in the way their dogs think and also to work with students who get really excited about the research. Who hasn't wondered, at least once, ‘what are animals thinking?’”

By Rachel McCarthy ’21