Elliott Notrica ‘26 first started making headlines with his cooking skill in 2013, when he was 10 years old.

As a small child, Elliott “started reaching for knives and lurching for knives and wanting to get a hold of the knives. And finally, my mom put her foot down and said, ‘Well, if you're so interested in knives, let's learn how to use them right,’” he told St. Louis’s local NBC news station at the time. Once he reached high school, Elliott was training with James Beard award winning chefs.

As a high school student brought into the world of St. Louis fine dining after winning multiple cooking competitions, Elliott couldn’t help but develop a passion for great food. As a student with a deep interest in science, he also couldn’t help coming up with ideas for how to make the vast industry of food production better.

Now, as a senior at Illinois Wesleyan, Elliott is the owner and CEO of his own food biotechnology company with two full-time employees and a newly assembled laboratory in one of Bloomington’s industrial parks.

* * *

The modern demand for high quality and visually appealing food comes with an unfortunate side effect: incredible amounts of food waste. Everything from undesirable byproducts, like shells and husks, to slightly bruised or over-ripe fruit can turn into mountains of discarded garbage. According to the US Department of Agriculture, between 30 and 40 percent of food produced in the US is wasted each year, which amounts to about 133 billion pounds.

While better food consciousness in American households would certainly help, much like CO2 emissions, the large majority of the problem comes from the industry rather than the consumer. When Elliott saw the volume of this problem first-hand in the restaurants of St. Louis, he knew he had an equally large opportunity.

“For some reason in America we’ve decided that the only thing you can do with food waste is use it as fertilizer or energy or put it in a landfill,” Elliott said. “It’s absurd.” It was obvious to him that there were much more creative uses for this resource that an enterprising organization could take advantage of.

“I started this almost four years ago,” Elliott said, referring to his biological engineering company Symbio Bioculinary. Note that Elliott is 22 years old as of fall 2025.

“Yeah, it was the year after I graduated from high school,” he confirmed. It was also after volunteering with World Central Kitchen to provide disaster relief in Ecuador and working with both a company in Los Angeles and the government of Ecuador to bring rare tropical fruits to the Los Angeles area.

Elliott took a gap year after graduating to found his business, which began as a one-man operation making traditional fermented food products out of food waste and excess food produced by local farms.

“But those aren’t scalable,” Elliott said. “And the only way to really have an impact on the food system is to do things at a large scale.”

So Elliott had to start thinking big.

* * *

“Fermentation is one of the few processes that can really chemically alter the composition of food,” Elliott said, expressing his admiration for the discipline. Through the careful use of what is essentially controlled rotting, it can turn grains and fruits into alcohols, milk into yogurt, yeast into sourdough or kombucha and any number of other food products into something that is both delicious and naturally preserved. “It’s central to the foods that all of us eat, so it’s a natural way to approach the issue of food waste.”

The problem with traditional methods of fermentation wasn’t just a matter of scale. Through thousands of years of trial, error and random chance, global cuisine had discovered at least hundreds of forms of fermentation. But those cooks were limited by the species of fungus and bacteria that existed in nature, evolving so that they happened to be able to transform one form of food into another via their natural processes. Those processes are just a matter of chemistry, and there’s no reason why these microbes couldn’t create thousands more foods for us to eat, especially if we weren’t going to eat the food that they were made of anyway. We only need to convince biology to cooperate.

Elliott came to IWU in 2022 as a biology major interested in fully understanding the world of fermentation. A few years later both he and the scientific world at large had the capacity to fulfill his vision.

“At some level, I understand it,” Elliott said of the incredible waste that the food industry tolerates. “Until recently, it was relatively hard to design the type of bio-processing systems that we’re creating and to do the type of bio-engineering that we’re doing, but it’s not anymore. The cost of genetic engineering has come down 100x in the last ten years. Now this is completely possible. ”

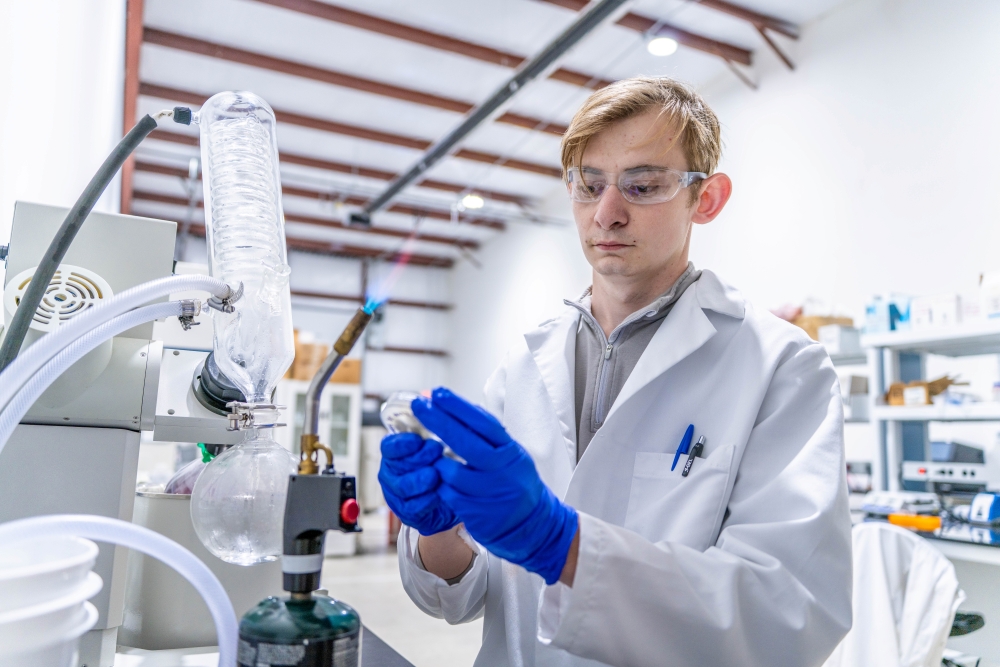

By “this” he wasn’t referring to the achievements of the world of science and engineering at large. He meant the achievements being made in the room in which he sat: Symbio’s own newly assembled genetic engineering and fermentation laboratory sandwiched between two auto shops in a Bloomington industrial park. The facility is equipped with a suite of technology capable of implementing the same kind of genetic engineering being done in industrial labs around the world, now available to a scrappy startup for a few hundred thousand dollars.

And by “we” he also wasn’t talking about a community of global scientists. He meant himself and his team of two full-time employees. Notably both of them had graduated from college with scientific degrees, but neither seemed bothered by having a boss who hadn’t yet walked at graduation himself.

At IWU, Elliott’s primary champion from the beginning was former director of the Petrick Idea Center John Quarton.

“I could see he was mature well beyond his years,” Quarton told WGLT in an interview about Elliott’s company and lab. “...he had this vision and this drive and this intelligence that blew me away for an undergrad, a freshman.”

“John was by far the best advocate I had on campus,” Elliott said.

* * *

As for Symbio’s business model, it’s shrouded in a veil of secrecy typical of technology companies, evidenced by the occasional answer of, “I can’t really talk about that yet,” when asked about the kinds of products they’re creating for clients.

As for what they are creating, “there wasn’t anyone doing what I wanted to do. There weren't any academic labs or any companies that were doing what we’re doing,” which is acting as a boutique engineer of microorganisms that turn a company’s food waste into new products. Once complete, rather than creating the food product themselves, they license the use of the microorganism as part of the company’s industrial process.

One frontier for the company is cocoa husks. Discarded in the process of turning cocoa beans into chocolate, these husks have long been used to make things like tea and artisanal flours, but large amounts are either added to mulch mixtures, thrown away or burned. A company that could invent a whole new use for this byproduct could save millions of pounds of food from becoming waste. And they might even do it before Elliott’s graduation in spring 2026.

“The sky's the limit for Symbio,” said Symbio investor and advisor Andrew Lusk. “Their fundamental product, upcycling of food waste, has potential clients in just about every agricultural and food manufacturing sector… As far as Elliott? With him at the helm, Symbio will no doubt chart a clear course towards success. I look forward to his future TED talk.”

The future of Symbio is shrouded in optimism and more than a little drive. But Elliott is at least able to provide some slight details about a bacteria that transforms unused dough into a sugary syrup that can be added back into the dough to improve taste, color and shelf-life. Still, it’s quickly evident to anyone visiting the Symbio lab that one is surrounded by trade secrets, any one of which might soon become a breakthrough.

“Huh, that kinda smells like meat,” said IWU photographer Adam Day while inspecting a dark liquid inside a beaker sitting inconspicuously on a countertop.

A slight nervous smile cracked on Elliott’s face in response, “Yeah, I can’t really talk about that.”