Waging War on COVID-19

Story by Matt Wing

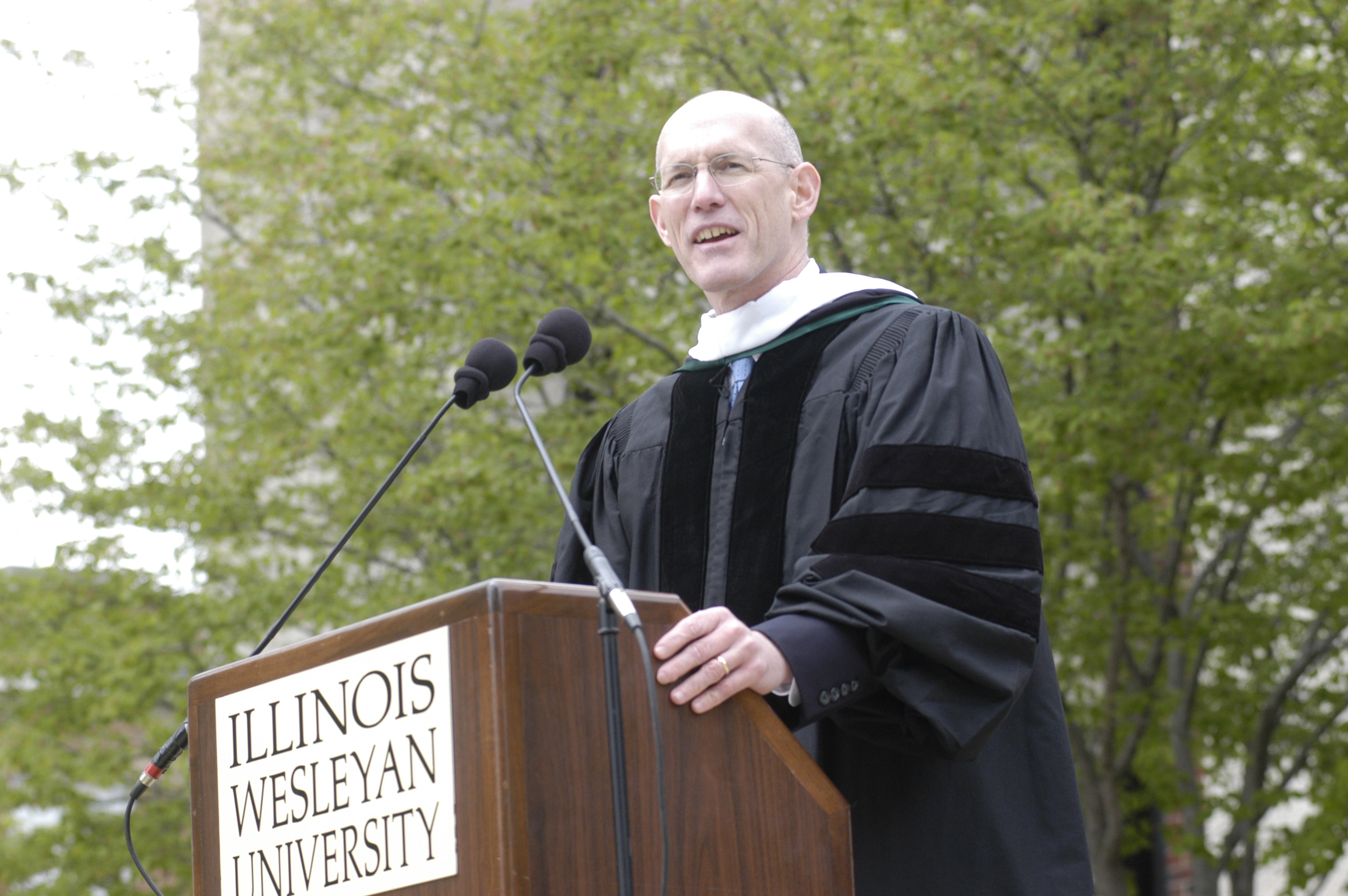

Dr. Gregory A. Poland ’77 has spent decades studying infectious diseases and developing vaccines, and is a leading voice during the current health crisis.

Dr. Gregory A. Poland ’77 first discovered an interest in medicine when, at the tender age of 4 years old, he severed the tip of a finger caught in a closing door.

As his mother and siblings scrambled to assist him, Poland calmly picked up the detached digit. He examined it. He watched the spurting blood. He was fascinated.

Poland’s mother rushed him to the nearby military hospital — the son of a career Marine, Poland and his family were then stationed in Hawaii — where a very green lieutenant sewed Poland’s finger back on. The lieutenant repeatedly shook his head as he performed the procedure without needing to anesthetize his young patient.

“I just sat there fascinated as he explained to me what he was doing,” Poland recalls. “I just watched and listened.”

So began a lifelong quest for knowledge and understanding. Shortly after that freak accident, Poland was given a chemistry set. He learned to make gunpowder to build rockets. He developed an interest, he reluctantly confesses, in dissecting small animals.

He would later prick his own finger to study his blood under a microscope he bought for $20, no small sum for a kid in the late 1960s. As a high school student, he found janitorial work in a medical building where he befriended physicians who lent him medical texts and reagents to stain his blood slides.

Poland eventually found his way to Illinois Wesleyan and, from there, to Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, the University of Minnesota and, eventually, Mayo Clinic. Today, he’s a prominent infectious diseases expert and vaccinologist with a long list of titles: a named professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Mayo Clinic; founder and director of Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group; Distinguished Investigator of the Mayo Clinic; and editor-in-chief of the medical journal Vaccine.

While many members of his family dedicated their lives to military service, Poland has dedicated his to fighting infectious diseases and developing vaccines for viruses like SARS-CoV-2, more commonly known as COVID-19, the novel coronavirus.

“My father, my brother and my middle son are all warriors who have served in the military,” Poland said. “My war has been infectious diseases.”

• • •

Two important things happened for Poland during his time at Illinois Wesleyan: he got his formal start in science and he met his future wife.

As a biology major, he was routinely challenged by professors like Bruce Criley, Harvey Beutner, Wendell Hess, Robert Hippensteele and Dorothea Frazen, who held students to what sometimes felt like impossibly high standards.

“I don’t think there was a single one of us who didn’t, at times, work in tears,” he said. “They demanded of us more than we even thought we had talent for, but it shaped us. I look back on this now, as almost a 65-year-old man, and I have used those lessons over and over in my career and teaching.”

But Poland’s education went far beyond the realm of science. He developed skills in writing and public speaking, critical thinking, and the ability to formulate and present arguments. He learned to question assumptions and dig for deeper meaning.

It all prepared him for what came next. “I didn’t know it at the time — we just whined about how hard we were being pushed — but I could not have been better prepared for medical school,” said Poland, who completed medical school in three years before an additional five years of training in internal medicine, clinical trials and infectious diseases.

Another perhaps more important development during Poland’s time at Illinois Wesleyan came on Friday, Sept. 12, 1975, around 8 p.m., on the steps of the Memorial Center. That’s when he met Jean Kunze ’79.

“I saw the most beautiful girl I had ever seen in my life,” Poland says between long pauses. “I felt paralyzed. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t walk. I fell head over heels in love.”

Poland and Kunze realized they were from the same hometown of Arlington Heights, Illinois. “I was from the poor side,” Poland said. “She from the side where if you needed braces and allergy shots, you could get them.” Kunze, a freshman nursing major, soon asked Poland for a ride back to their hometown. With hardly enough gas money in his pocket, an excited Poland quickly agreed. The relationship officially began.

A couple months from now they’ll celebrate the 45th anniversary of that night on the steps of the Memorial Center.

“I think it was that night — my wife says it was a few nights after that — when I asked what she would think if I asked her to marry me,” Poland said. “I absolutely knew when I looked over at her and couldn’t breathe that night that this was the woman I was going to marry.”

• • •

Poland’s expertise in the field of infectious diseases and vaccinology began with a series of events during his residency.

There was the man with tetanus who suffered permanent neurological damage. There was the HIV-positive woman some doctors were hesitant to treat at the outset of the AIDS epidemic when little was known about the virus. There was the newborn child with a bacterial form of meningitis who became permanently deaf.

And then a personal bout with the flu provided him a firsthand experience.

“I just kept thinking ‘How are all of these diseases possible?’ ” Poland said. “We know how to prevent them!”

Poland declared war on infectious diseases. Over the next four decades, he became an internationally prominent infectious diseases expert and vaccinologist. He’s won numerous awards and grants, and published nearly 700 scientific papers on his findings. He’s been an outspoken advocate for mandatory flu shots and inspired the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation for all persons over the age of six months to receive one. Poland is a past president of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board and was appointed by President George W. Bush to two terms as president of the Health Defense Board. President Bush and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld awarded him the highest civilian medal for his work in biodefense and infectious diseases prevention, the Secretary of Defense Medal for Outstanding Public Service. The National Institutes of Health awarded him a MERIT Award given to less than 2% of federally funded researchers.

“I’ve had the opportunity to be in the right place at the right time, with the right training to use all the things that I have learned in my life,” he said.

Poland founded and continues to lead the Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group, which is one of more than 100 teams working on a COVID-19 vaccine. Poland has cautioned against rushing a vaccine to market, however, without following the necessary scientific and regulatory pathways. He specifically used the fable of The Tortoise and the Hare in framing an editorial to this point published in Vaccine.

Poland attempts to inform the public through frequent appearances in news media all over the world. “I’ve been trying to shape and lead public policy by being a voice putting forward the science in an honest and transparent way that is digestible for the general public,” he said.

Poland furthermore provides leadership through his role as a professor at Mayo Clinic where he mentors students much in the same way he was mentored at Illinois Wesleyan.

“It’s pretty special to be a part of that circle where you’ve had those types of mentors and now you get to pass it on to the next generation,” he said.

• • •

In the past few months, Poland has been asked over and over, “When are we going to get back to normal?”

His simple answer is: we won’t.

Poland believes fundamental change will come from the COVID- 19 pandemic, extending far beyond increasing usage of face masks and discontinuing the practice of shaking hands. Shopping and procuring food and goods will change. Ways in which we participate in religious life will change. Actions as simple as visiting a public restroom will change.

And, yes, higher education will change.

“I really can’t think of a domain that won’t legitimately be changed,” Poland said. “While there may be a window in which things ‘go back to normal’ during the summer, it will only be temporary.”

That potential return to normalcy is perhaps one of the scariest aspects of the pandemic, Poland suggests. As we become numb to the reality of living in a world threatened by a pandemic, the lessons learned begin to fade and history becomes more likely to repeat itself.

Poland points to a cautionary tale of systemic failure included in the 9/11 Commission Report, which identified lack of imagination as one key area of failure.

“Though we had been warned multiple times, we failed to believe those warnings, and therefore we could not imagine it happening and failed to prepare,” he said.

Poland has seen the same absence of imagination in planning for pandemics. He’s taken part in tabletop exercises addressing pandemics, where the lack of planning has been exposed and the inability of governments to adapt and cooperate often leave the world in a state of anarchy.

Poland all but guarantees there will be a second wave of COVID-19 this winter, which will be complicated by flu season running concurrently. He anticipates future coronaviruses like COVID-23 and COVID- 28. He admits little is known about the long-term impact on individuals who have been infected and recovered from COVID-19.

It can all be a little overwhelming, Poland admits, and while the lessons learned at Illinois Wesleyan have guided him in his work, the woman he met there has helped keep him sane by providing moments of levity.

Poland jokes that he awoke one morning recently with his wife gently pressing a pillow over his face. Startled, he scrambled to his feet and asked her what she was doing. “She told me she loved me so much that she didn’t want me to breathe in the coronavirus,” Poland said, laughing.

Those moments, and an earnest desire to save lives and prevent disease, give Poland the strength to carry on. His lab is hard at work developing a unique COVID-19 vaccine, while he continues informing the public on the dangers of viruses like COVID-19 and the repercussions of lacking imagination.

“We’re not going to have a vaccine by this fall — certainly not one that has been safety-tested — and we’re in danger of replaying everything we’ve just been through, and there’s only one reason: imaginability,” Poland said. “We could have and should have had diagnostics, antivirals and vaccines stretching back for years — after all, we have had three novel coronaviruses jump the species barriers into humans in the last 18 years — but we don’t take these threats seriously.

“And that’s my war.”