Protecting the Vulnerable

Story by Matt Wing

Illinois Wesleyan 2020 Distinguished Alumni Award winner Dr. Raymond “Pete” Davis ’80 treats and advocates for victims of child abuse and child sexual abuse.

Dr. Raymond “Pete” Davis ’80 has been a pediatrician long enough he is occasionally asked what it’s like to treat a second generation of patients.

He laughs before answering. “I’m actually treating the grandkids now,” he says.

Davis has impacted thousands of lives in Rockford, Illinois, where he has practiced for nearly a third of a century. One of the greatest compliments he is paid is when former patients trust him with their children.

“It’s a great feeling when someone you took care of as a child thinks enough about the care you gave them and felt comfortable and liked you enough that they want to bring their kids to see you,” he said.

Davis treats a largely vulnerable population on Rockford’s west side where nearly half his patients are Medicaid recipients. But through expertise he’s gained over decades of treating patients, and by seeking additional training and certifications, he has increasingly treated and advocated for the most vulnerable population among us.

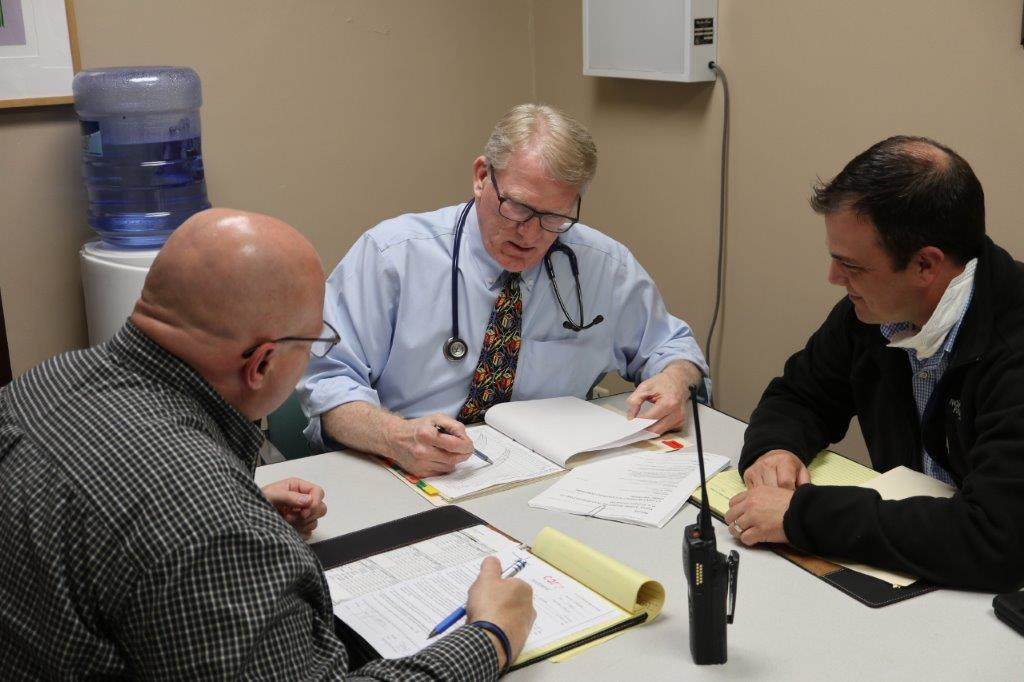

Davis is a leading expert in child physical and sexual abuse who regularly assists law enforcement and social services in efforts to protect and advocate for victims of abuse.

Dr. Raymond Davis is the recipient of Illinois Wesleyan’s 2020 Distinguished Alumni Award.

“I’m extremely honored and extremely humbled,” he said. “The Lord gave me a brain, Wesleyan gave me a tremendous education, and I found an area that I like to use them.”

• • •

Raymond Davis loved school. He enjoyed science and showed an early interest in medicine. He was inspired when he toured a local hospital and when he attended a presentation from a world-renowned cardiovascular surgeon, where he stuck out as the lone high school student in an audience of healthcare professionals.

Throughout his formative years, campus visits were incorporated into Davis family vacations. He visited Harvard, Yale and others. On the advice of a family friend, he was encouraged to consider Illinois Wesleyan. “He said if you are really interested in medicine, that Wesleyan was the place to go,” Davis recalled. “He said if you could get through Wesleyan’s pre-med program, you were going to go to medical school.”

Davis investigated and found that nearly all IWU biology graduates found placement in medical or dental school. “How do you not go to a school like that?” he said.

At Illinois Wesleyan, Davis found professors who pushed him hard while also providing guidance and mentoring. That, combined with his love of learning, led him to a triple major in biology, chemistry and physics.

He was admitted to the University of Illinois College of Medicine, where he found himself uniquely prepared. “Wesleyan was a great preparatory school because it took a lot of work if you were going to be successful,” Davis said. “I’m not sure I’d have made it through medical school without Wesleyan.”

Along the way, Davis discovered a passion for pediatrics. He enjoyed previous experiences as a youth baseball and swimming coach and, as he explored different areas of medicine, his preferred field became quite clear.

“I’d always enjoyed working with kids. Pediatrics was very rewarding, very fulfilling,” Davis said. “It was fun when you could get a little kid who didn’t feel good to smile.”

Davis completed his residency at OSF St. Francis Medical Center in Peoria, Illinois, and, after a year in Lafayette, Indiana, returned to Illinois and began practicing as a pediatrician at Rockford Clinic (now part of the Mercyhealth System), where he has remained since 1988.

Experiences with child abuse early in Davis’ career made an impact on the young doctor. In the first year after his residency, he testified in court cases of child abuse and medical neglect. He attended a police presentation on forensic interviewing of potential victims. With minimal child abuse training during his residency, he conducted independent study and devoured the little research available on the topic.

Legislation was soon passed that required counties to develop protocol for handling allegations of sexual abuse, and Davis was asked to help plan a children’s advocacy center for Winnebago (Ill.) County. Two years later, the county opened its center in a temporary space but soon moved into a dedicated, child-friendly building with space for interviews, law enforcement, state’s attorneys and social services. Davis was named medical director at the facility where he examined patients and eventually recruited and trained five other doctors to help with exams.

Law enforcement and Department of Child and Family Services officials, knowing when and where they could find Davis, soon began stopping by the center with photographs of suspected abuse. Davis was asked to provide an opinion on the spot, with limited information, in what he called “curbside consults.” Knowing that it could be done better, he approached DCFS and the University of Illinois College of Medicine Rockford with a proposal for a formal child protection service. Both were receptive and the UICMR’s Medical Evaluation Response Initiative Team (MERIT) opened in 2008. It was at this time that Davis joined the faculty of the University of Illinois College of Medicine and started working toward becoming a board-certified child abuse pediatrician. He earned his certification in 2013 after passing the board exam, and became one of only 13 child abuse pediatricians in the state.

More legislation requiring local governments to address child physical and sexual abuse put Davis’ expertise in high demand, and nearby counties called on him to help meet new standards. He now serves as the medical director for advocacy centers in seven northern Illinois counties and provides training to law enforcement, state’s attorneys and DCFS officials in 15 counties.

“I was happy doing my bit in my own little part of the world. The only desire I had initially was to do the best I could in my own practice,” Davis said. “I didn’t anticipate ever being where I am right now.”

• • •

Normally, a decrease in reported abuse cases would be good news for Davis. But in the time of COVID-19, it’s not necessarily a good thing. Far from it, actually.

Davis knows better than to celebrate the decline in reported cases. He knows it’s likely the result of children being out of schools, day cares and other activities in the company of adults who typically report abuse.

“It’s really scary to think what might be happening to these kids because they are sheltering at home with potential perpetrators,” Davis said. “This time has really showed how important our teachers are.”

Like healthcare workers all over the world, Davis is working through the COVID-19 pandemic and continuing to provide a high level of care. And he’s continued to be a leading voice in combatting child abuse and child sexual abuse, specifically as a mentor to the next generation advocating for children.

“It takes lots of people to be on guard and watching out for these kids,” he said. “I think the biggest part of my job now is educating my colleagues on the front line.”

Though his age might suggest retirement is on the horizon, Davis insists that he won’t leave his program until a full-time child abuse pediatrician can be hired to replace him. Nor is he ready to retire from his general practice, which has often served as a comforting retreat from his work with victims of abuse.

Being able to make a sick kid smile gives Davis the boost he needs to continue his work.

“The general pediatrics part keeps me from getting burned out because it really can get overwhelming,” he said. “It helps keep me grounded and keeps me focused, which helps me to do better with the child abuse part, and gives me energy to keep going.”